Genre fictions serve very real purposes. Comedies, of course, make life more bearable by making us laugh at the incongruencies we come up against in everyday life. Sword and sorcery fiction allows readers to escape from the ugliness of the real world by immersing them in fictional geographies inhabited by fictional species who speak fictional languages. Horror allows us to confront our anxieties and fears in a way that is viscerally thrilling, but entirely safe. Science-fiction functions in a similar vein to horror, but it is commonly more cerebral, and has, at its core, humanity’s inherent distrust of, and resistance to, technological advancements.

It can be difficult for modern audiences to take works of science-fiction seriously when they begin to feel dated, and ultimately, more of a reflection of their own time than the futurous worlds that they predicted. But every now and again, something will happen in the real world that is uncanny in it’s resemblance to fictional works of generations passed.

Here is a look at two seminal works of science-fiction, written decades ago, but startlingly relevant today nevertheless.

“August 2026: There Will Come Soft Rains”

Ray Bradbury

A striking and all too frequently overlooked short by Ray Bradbury, who was one of America’s pre-eminent authors of science-fiction and horror literature during the height of cold war era. August starts off by describing a fully automated house, which prepares meals, deliver vocal messages through an intercom, and generally takes care of itself and the family which occupies it. The family, however, is strangely absent.

The novel parses out details as the story progresses. We read that a baseball has burned into the side of the home, and we hear that there are silhouettes permanently burned into the walls of the home — which quickly summon to mind the horror stories of the bombing campaigns in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Bear in mind that this story was first published in 1949, a mere four years after the bombs were dropped, and the horrors of World War II were fresh in the collective consciousness.

It’s all the more chilling because it is unclear to the reader how much time has passed between whatever nuclear holocaust has taken place and the principal action of the story. Has the house been mechanically carrying out its duties for two days, or 25 years?

One thing that’s really great about the story is that it juxtaposes utilitarian, consumer driver applications of technology — things which do afford humanity certain conveniences — with the harmful, potentially genocidal applications of technology.

It also calls to mind all of the recent news items we’ve been reading about home automation advancements in the tech field now — complex systems relying upon “smart” appliances which communicate via smart phone platforms. What happens when the very same ingenuity that goes into designing these systems is applied to decimating an entire civilization? Are these luxuries worth it, if the advancements that make them possible also enable super powers to kill people in droves?

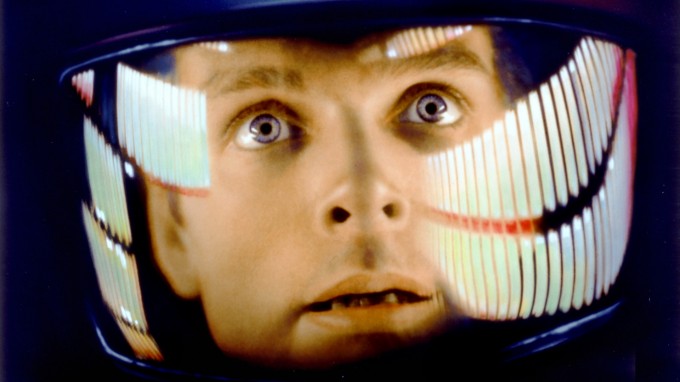

“2001: A Space Odyssey”

Arthur C. Clarke

This was a monumental piece of pop literature, which informed the classic Stanley Kubrick film by the same name (which, if you haven’t already seen, you really must immediately). Clarke was a true visionary who contributed much more to the world than speculative fiction — he actually anticipated geosynchronous satellite communication networks as early as 1945– 12 years before the launch of Sputnik. Clarke’s writings reflect his keen interest in technology, and the degree to which it has reshaped human life. The book starts off at the very beginning stages of humanity — more precisely, it starts with our remote ancestors (apes) conceiving of the notion of a utility or tool. The birth of modernity is the ape realizing that he can hunt with a bone. This is the basis for technology — sentient beings on earth realizing the degree to which they can alter their environment. We flash forward a few millennia to the year 2001, where a team of astronauts are flying to Jupiter’s moon in a spaceship that is equipped with supremely sophisticated artificial intelligence — the infamous HAL 9000. When technical difficulties prompt the astronauts aboard the ship to abandon their mission, HAL sets about killing them off, in order to fulfill the mission.

Like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis before it, the novel poses the question of what happens when inanimate objects are imbued with supreme intelligence, without the moral agency and compassion which humans are naturally endowed with, and which society (ideally speaking at least) strives to foster. It’s a dark meditation on the potentially catastrophic (intended or unintended) consequences of technology, and it makes readers feel much more vulnerable about their existence within a society that has become largely dependant upon machines. What happens when the machines become too intelligent for our own good? Imagine what will happen when our GPS platforms start commanding us to drive off of cliffs — or ponder the potential harm that a smart toaster gone haywire could cause.

These are extremely important works from some of the 20th centuries most fascinating minds. If you haven’t read both yet, you would be wise to do so.

Need More Science Literature?

As we all know, sometimes fiction inspires life, and the other way around – and that is no different when it comes to science fiction and actual REAL Science. If you still need to fill in that science craving all us geeks have with more science related literature (some of it seems stranger than science fiction) here is a list of some of the greatest science books ever written in our time, enjoy!

25 Great Books By Legendary Scientists

100 All-Time Greatest Popular Science Books (and 17 More)

100 Most Influential Books of the Century