The leap from prototype to production is rarely a straight line, especially in hardware. Founders often underestimate the complexity of manufacturing, assuming that a working prototype means they’re nearly ready to scale. In reality, small oversights at this stage can turn into weeks of delays, unexpected costs, or units that fail quality checks on arrival.

Manufacturing physical products, unfortunately, isn’t solely about design; it’s also about documentation, partner selection, tolerance management, and timeline discipline. A single bottleneck, like a part requiring a nonstandard finish, can throw off your schedule by months. That’s why founders need more than a great idea; they need a practical understanding of how to transition that idea into a repeatable, manufacturable product.

Below, you’ll find our founder’s guide to manufacturing hardware products, covering the essentials you’ll need to build successfully from the ground up.

Finalize Your Functional Design

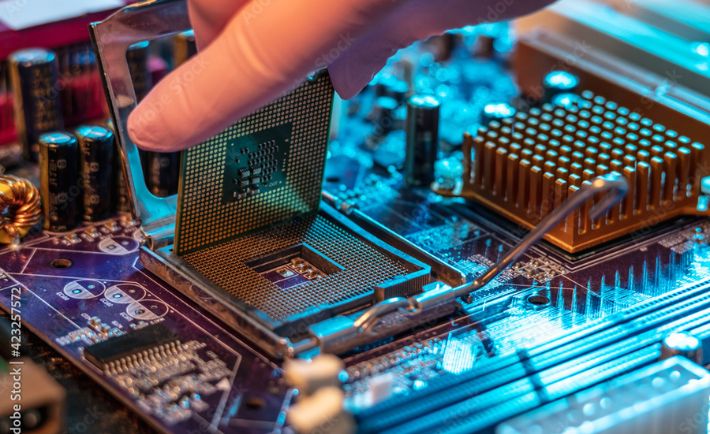

Before you approach any manufacturer, your product design should be completely locked in. This includes electrical layouts, mechanical tolerances, connector types, and enclosure specifications. Also, check connector alignment, PCB mounting points, airflow paths, and internal cable routing, as these are small layout decisions that affect heat dissipation, serviceability, and long-term reliability.

Too many founders jump into production with vague drawings or half-tested subsystems, assuming they’ll finalize things on the fly. That flexibility disappears the moment you commit to tooling.

One effective strategy is to build a single working unit using off-the-shelf components that most closely match your intended production materials. This preproduction prototype doesn’t need to be perfect, but it should operate under real-world conditions. Use it to test thermal behavior, structural integrity, and internal fit. You’ll want to catch design flaws now, well before you’re $20,000 into an injection mold.

Understand Manufacturing Readiness

Think of manufacturing readiness as a checklist. At minimum, you’ll need detailed 2D drawings with tolerances, a full bill of materials (BOM) with sourcing information, and a digital 3D model of your assembly. Most contract manufacturers also expect some form of DFMA review, which ensures the design can be assembled efficiently at scale.

Every extra part or feature comes at a cost. Integrating a custom-milled aluminum bracket might look nice, but it could add $30 per unit and three extra weeks of lead time. A designer who doesn’t understand production realities might spec powder-coated steel when folded sheet metal would perform the same function for half the cost. Each detail matters more than most early-stage teams realize.

Choose the Right Manufacturing Partner

Speed and price can be tempting, but they’re poor metrics for selecting a manufacturing partner. Founders who rush this step often regret it. Look beyond price quotes. Ask for references, request sample parts, and evaluate how well a vendor communicates. A partner who responds clearly within 24 hours is worth far more than one who disappears mid-production.

Not all manufacturing partners offer the same scope either. Contract manufacturers handle everything from sourcing to final assembly. Original design manufacturers (ODMs) provide design input but may limit you to preconfigured templates. Job shops handle small, specialized runs ideal for pilot testing, but they’re often unsuitable for high-volume work. The best fit depends on the complexity of your product and its target market.

Prototype Using Scalable Methods

Rapid prototyping is essential for testing ideas quickly, but not all prototyping methods scale well. Using SLA resin or 3D-printed plastics might help validate form and fit, but these materials rarely match the strength, heat resistance, or finish quality needed for production. Relying too heavily on these methods can lead to unexpected challenges during the transition to mass manufacturing.

At this stage, it helps to understand popular CNC machining methods and materials, as they offer a clear bridge between prototyping and full-scale production. CNC parts made from aluminum, ABS, or acetal often mirror final production specs closely enough to test for durability, thermal behavior, and tolerance stacking. They also help identify the need for early design changes before you commit to expensive tooling.

Plan for Tooling and Lead Times

Tooling always takes longer than you think. A basic aluminum injection mold might take six weeks, but multicavity or steel molds can stretch to 10 or more. Costs also scale quickly. These are sunk costs; changing the design post-tooling often means starting over.

Terms like pilot run and golden sample become relevant in this context. A golden sample is your approved benchmark; everything else must match it. A pilot run (often 100 to 500 units) validates your tooling, assembly workflow, and packaging. Every tweak after this stage adds not only time but also risk. That’s why locking your design down to the last screw length is imperative before tooling begins.

Build for Assembly and Testing

Creating parts that look good on their own isn’t the same as building a product that assembles cleanly and reliably. Assembly adds constraints. Will wires reach their connectors? Can the unit be closed without pinching anything? Founders often miss these questions until their first hundred units are on the bench. It’s more efficient to answer them on paper and in your prototype.

Functional testing matters, too. A manual five-minute test per unit doesn’t scale if you’re building 10,000 devices—that’s 833 labor hours. Start by defining what success looks like: Does the screen light up? Does the motor spin without stutter? Are firmware updates installing correctly through your intended interface?

From there, design repeatable test procedures. Whenever possible, automate steps and integrate test points directly into the hardware.

Watch Your Unit Economics Early

Margins shrink over time. It’s not just about your bill of materials (BOM); shipping costs, packaging, regulatory testing, firmware support, and returns all eat away at what you thought was a healthy profit. Founders often set prices based on rough estimates, only to discover that their real-world costs don’t leave enough room for distribution, marketing, or customer support. A founder’s guide to manufacturing hardware products wouldn’t be complete without one last piece of advice: Start tracking real-world per-unit costs before your first production run. It’s far easier to price correctly early on than to backpedal later. Consider every recurring cost—from screws to support tickets—and build in enough margin to survive version two.